Light Blending In – Moontide

Moontide

Light Blending In

February 22, 2026

January 24, 2026

Tracks in this feature

Tracks in this release

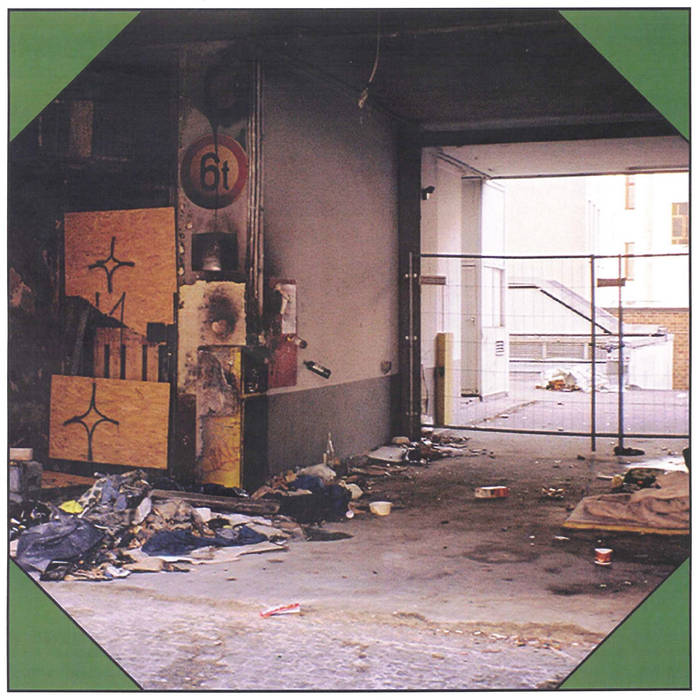

At first glance, Release the Beast appears to sit comfortably alongside the industrial IDM output of the Hymen Records catalogue, echoing the stark visual language associated with artists such as Keef Baker and Somatic Responses. With cover art depicting the boarded-up stairwell of a former Berlin nightclub, Dennis Schulze’s sixth album – made under the CV Vision moniker – arrives framed by imagery that suggests a cold, analytical engagement with technological decay and obsolete media.

Yet what the record delivers is something far less austere: Release the Beast unfolds as a richly detailed and almost paradoxically nostalgic work that treats genre fusion as its central organising principle. This approach is rooted in the album’s creative process, which Schulze describes as akin to assembling Frankenstein. “I dug out my two broken reel-to-reel tape machines and patched them together,” he explains. “There are different musical styles, but it’s the tape machine that brings it all together, sound-wise.”

Built from tape loops, library music fragments, meandering guitar riffs, indie-pop timbres, and 8-bit arcade ephemera, Release the Beast indeed sounds like the product of an obsessive crate-digger armed with a four-track tape machine and little interest in historical purity. 1960s psych bleeds into turn-of-the-millennium indie rock, while degraded digital artefacts sit comfortably alongside analog fuzz.

The album is unapologetically derivative, but crucially, it understands derivation as a creative act rather than a failure of originality. In doing so, it challenges the listener to consider whether the cultural references it draws upon ever existed as such, or whether they might be more accurately understood as second-hand constructions shaped by mediation and reinterpretation.

The record’s thesis is laid out most clearly in its opening sequence. RTB unfolds as a collage of Hendrix-inflected guitar loops, musique concrète-style noise flourishes, and early Moog gestures reminiscent of Jean-Jacques Perrey. These elements place the listener within a romanticised vision of 1960s psychedelia that is, nonetheless, entirely imagined. Its nod to the past functions much like a vintage filter applied to a contemporary photograph: the technological mediation is unmistakable, yet the soft focus it produces remains persuasive.

That reverie is abruptly disrupted by the transition into The Rhythm, which yanks the album forward three decades. Knowingly saccharine lyrics blend late-’90s Britpop with turn-of-the-century American indie rock à la Julian Casablancas, conjuring a hazy vision of adolescence as a space of heightened feeling and faint self-consciousness in equal measure (“how can I be sure that I’m not dreaming?” the song repeatedly asks). The track’s title encapsulates this tension, implying that the rhythms of adolescence resist precise musical or linguistic mapping and instead manifest as something deliberately opaque – an unmistakable, if impossible, vibe.

This temporal slippage continues throughout the album. Nikitas Tune pairs Connan Mockasin-style slackened guitar work with Haight-Ashbury folk-rock tropes, producing a strangely convincing memory of experiences never actually lived. The track’s minimal tonal progression is layered with analog fuzz and delay-drenched drone pads, offering a textbook example of hypnagogic pop’s capacity to evoke feeling without narrative: reverb and temporal stretching give the past a quality of immediacy and intimacy, even when (and maybe because) it is borrowed wholesale.

Block Rock pushes this logic further, drawing heavily from early arcade game soundtracks. Rather than simply leaning into chiptune pastiche, Schulze nonetheless smothers these 8-bit motifs in tape saturation, blurring their outlines until they register more as sensation than reference. The track reinforces the album’s central mood, best described as a pleasant oscillation between clarity and blur.

The closing track, Go Your Way, gathers the album’s influences into a loose, woozy send-off. Psychedelic rock, krautrock, and kosmische musik converge in a haze of tape hiss, wandering guitar lines, and deliberately unpolished performance. At times, it recalls a particularly unfocused Mac DeMarco set; at others, a degraded echo of Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds. The return of vocals, previously submerged beneath the album’s instrumental wanderings, underscores the central tension between presence and absence that defines Schulze’s work. It also prompts questions about how much the human hand behind this newly assembled Frankenstein shapes – or even explains – the creation itself.

As with many artists working in comparable cultural terrains (Oneohtrix Point Never chief among them), CV Vision treats nostalgia as both subject and creative method. Listening to Release the Beast thus evokes a dual awareness: an appreciation for the music’s creative imperfections alongside the recognition that this honesty is always already filtered through refracted cultural references. In this sense, Schulze’s achievement lies less in forging something entirely new from his influences than in capturing the distinctly contemporary experience of encountering culture second-hand.